Chapter Summary: The first half of this chapter attempts to define music as a subject and offers perspectives on music, including basic vocabulary and what you should know about music in order to incorporate it in your work with children. The second half gives a brief overview of music education and teaching in the U.S., which provides the foundation of the discipline for the book.

I. Defining Music

“Music” is one of the most difficult terms to define, partially because beliefs about music have changed dramatically over time just in Western culture alone. If we look at music in different parts of the world, we find even more variations and ideas about what music is. Definitions range from practical and theoretical (the Greeks, for example, defined music as “tones ordered horizontally as melodies and vertically as harmony”) to quite philosophical (according to philosopher Jacques Attali, music is a sonoric event between noise and silence, and according to Heidegger, music is something in which truth has set itself to work). There are also the social aspects of music to consider. As musicologist Charles Seeger notes, “Music is a system of communication involving structured sounds produced by members of a community that communicate with other members” (1992, p.89). Ethnomusicologist John Blacking declares that “we can go further to say that music is sound that is humanly patterned or organized” (1973), covering all of the bases with a very broad stroke. Some theorists even believe that there can be no universal definition of music because it is so culturally specific.

Although we may find it hard to imagine, many cultures, such as those found in the countries of Africa or among some indigenous groups, don’t have a word for music. Instead, the relationship of music and dance to everyday life is so close that the people have no need to conceptually separate the two. According to the ethnomusicologist Bruno Nettl (2001), some North American Indian languages have no word for “music” as distinct from the word “song.” Flute melodies too are labeled as “songs.” The Hausa people of Nigeria have an extraordinarily rich vocabulary for discourse about music, but no single word for music. The Basongye of Zaire have a broad conception of what music is, but no corresponding term. To the Basongye, music is a purely and specifically human product. For them, when you are content, you sing, and when you are angry, you make noise (2001). The Kpelle people of Liberia have one word, “sang,” to describe a movement that is danced well (Stone, 1998, p. 7). Some cultures favor certain aspects of music. Indian classical music, for example, does not contain harmony, but only the three textures of a melody, rhythm, and a drone. However, Indian musicians more than make up for a lack of harmony with complex melodies and rhythms not possible in the West due to the inclusion of harmony (chord progressions), which require less complex melodies and rhythms.

What we may hear as music in the West may not be music to others. For example, if we hear the Qur’an performed, it may sound like singing and music. We hear all of the “parts” which we think of as music—rhythm, pitch, melody, form, etc. However, the Muslim understanding of that sound is that it is really heightened speech or recitation rather than music, and belongs in a separate category. The philosophical reasoning behind this is complex: in Muslim tradition, the idea of music as entertainment is looked upon as degrading; therefore, the holy Qur’an cannot be labeled as music.

Although the exact definition of music varies widely even in the West, music contains melody, harmony, rhythm, timbre, pitch, silence, and form or structure. What we know about music so far…

- Music is comprised of sound.

- Music is made up of both sounds and silences.

- Music is intentionally made art.

- Music is humanly organized sound (Bakan, 2011).

A working definition of music for our purposes might be as follows: music is an intentionally organized art form whose medium is sound and silence, with core elements of pitch (melodyand harmony), rhythm (meter, tempo, and articulation), dynamics, and the qualities of timbre and texture.

Beyond a standard definition of music, there are behavioral and cultural aspects to consider. As Titon notes in his seminal text Worlds of Music(2008), we “make” music in two different ways: we make musicphysically; i.e., we bow the strings of a violin, we sing, we press down the keys of a piano, we blow air into a flute. We also make music with our minds,mentally constructing the ideas that we have about music and what we believe about music; i.e., when it should be performed or what music is “good” and what music is “bad.” For example, the genre of classical music is perceived to have a higher social status than popular music; a rock band’s lead singer is more valued than the drummer; early blues and rock was considered “evil” and negatively influential; we label some songs as children’s songs and deem them inappropriate to sing after a certain age; etc.

Music, above all, works in sound and time. It is a sonic event—a communication just like speech, which requires us to listen, process, and respond. To that end, it is a part of a continuum of how we hear all sounds including noise, speech, and silence. Where are the boundaries between noise and music? Between noise and speech? How does some music, such as rap, challenge our original notions of speech and music by integrating speech as part of the music? How do some compositions such as John Cage’s 4’33’’ challenge our ideas of artistic intention, music, and silence?

Basic Music Elements

- Sound (overtone, timbre, pitch, amplitude, duration)

- Melody

- Harmony

- Rhythm

- Texture

- Structure/form

- Expression (dynamics, tempo, articulation)

In order to teach something, we need a consensus on a basic list of elements and definitions. This list comprises the basic elements of music as we understand them in Western culture.

1. Sound

Overtone: A fundamental pitch with resultant pitches sounding above it according to the overtone series. Overtones are what give each note its unique sound.

Timbre: The tone color of a sound resulting from the overtones. Each voice has a unique tone color that is described using adjectives or metaphors such as “nasally,” “resonant,” “vibrant,” “strident,” “high,” “low,” “breathy,” “piercing,” “ringing,” “rounded,” “warm,” “mellow,” “dark,” “bright,” “heavy,” “light,” “vibrato.”

Pitch: The frequency of the note’s vibration (note names C, D, E, etc.).

Amplitude: How loud or soft a sound is.

Duration: How long or short the sound is.

2. Melody

A succession of musical notes; a series of pitches often organized into phrases.

3. Harmony

The simultaneous, vertical combination of notes, usually forming chords.

4. Rhythm

The organization of music in time. Also closely related to meter.

5. Texture

The density (thickness or thinness) of layers of sounds, melodies, and rhythms in a piece: e.g., a complex orchestral composition will have more possibilities for dense textures than a song accompanied only by guitar or piano.

Most common types of texture:

- Monophony: A single layer of sound; e.g.. a solo voice

- Homophony: A melody with an accompaniment; e.g., a lead singer and a band; a singer and a guitar or piano accompaniment; etc.

- Polyphony: Two or more independent voices; e.g., a round or fugue.

6. Structure or Form

The sections or movements of a piece; i.e. verse and refrain, sonata form, ABA, Rondo (ABACADA), theme, and variations.

7. Expression

Dynamics: Volume (amplitude)—how loud, soft, medium, gradually getting louder or softer (crescendo, decrescendo).

Tempo: Beats per minute; how fast, medium, or slow a piece of music is played or sung.

Articulation: The manner in which notes are played or words pronounced: e.g., long or short, stressed or unstressed such as short (staccato), smooth (legato), stressed (marcato), sudden emphasis (sforzando), slurred, etc.

What Do Children Hear? How Do They Respond to Music?

Now that we have a list of definitions, for our purposes, let’s refine the definition of music, keeping in mind how children perceive music and music’s constituent elements of sound (timbre), melody, harmony, rhythm, structure or form, expression, and texture. Children’s musical encounters can be self- or peer-initiated, or teacher- or staff-initiated in a classroom or daycare setting. Regardless of the type of encounter, the basic music elements play a significant role in how children respond to music. One of the most important elements for all humans is the timbre of a sound. Recognizing a sound’s timbre is significant to humans in that it helps us to distinguish the source of the sound, i.e. who is calling us—our parents, friends, etc. It also alerts us to possible danger. Children are able to discern the timbre of a sound from a very young age, including the vocal timbres of peers, relatives, and teachers, as well as the timbres of different instruments.

Studies show that even very young children are quite sophisticated listeners. As early as two years of age, children respond to musical style, tempo, and dynamics, and even show preference for certain musical styles (e.g., pop music over classical) beginning at age five. Metz and his peers assert that “a common competence found in young children is the enacting through movement of the music’s most constant and salient features, such as dynamics, meter, and tempo” (Metz, 1989; Gorali-Turel, 1997; Chen-Hafteck, 2004). On the aggregate level, children physically respond to music’s beat, and are able to move more accurately when the tempo of the music more clearly corresponds to the natural tempo of the child. As we might expect, children respond to the dynamic levels of loud and soft quite dramatically, changing their movements to match changing volume levels.

The fact that children seem to respond to the expressive elements of music (dynamics, tempo, etc.) should not come as a surprise. Most people respond to the same attributes of music that children do. We hear changes in tempo (fast or slow), changes in dynamics (loud or soft), we physically respond to the rhythm of the bass guitar or drums, and we listen intently to the melody, particularly if there are words. These are among the most ear-catching elements, along with rhythm and melody.

This is what we would expect. However, there are other studies whose conclusions are more vague on this subject. According to a study by Sims and Cassidy, children’s music attitudes and responses do not seem to be based on specific musical characteristics and children may have very idiosyncratic responses and listening styles (1997). Mainly, children are non-discriminating, reacting positively to almost any type of music ...

Music Teaching Vocabulary

After familiarizing yourself with the basic music vocabulary list above (e.g., melody, rhythm), familiarize yourself with a practical teaching vocabulary: in other words, the music terms that you might use when working in music with a lesson for children that correspond to their natural perception of music. For most children, the basics are easily conveyed through concept dichotomies, such as:

- Fast or Slow (tempo)

- Loud or Soft (dynamics)

- Short or Long (articulation)

- High or Low (pitch)

- Steady or Uneven (beat)

- Happy or Sad (emotional response)

Interestingly, three pairs of these dichotomies are found in Lowell Mason’s Manual for the Boston Academy of Music (1839).

For slightly older children, more advanced concepts can be used, such as:

- Duple (2) or Triple (3) meter

- Melodic Contour (melody going up or down)

- Rough or Smooth (timbre)

- Verse and Refrain (form)

- Major or Minor (scale)

Music Fundamentals

The emotive aspects of music are what most people respond to first. However, while an important part of music listening in our culture, simply responding subjectively to “how music makes you feel” is similar to an Olympic judge saying that she feels happy when watching a gymnast’s vault. It may very well be true, but it does not help the judge to understand and evaluate all of the elements that go into the execution of the gymnast’s exercise or how to judge it properly. Studies show that teachers who are familiar with music fundamentals, and especially note reading, are more comfortable incorporating music when working with children (Kim, 2007). Even just knowing how to read music changes a teacher’s confidence level when it comes to singing, so it’s important to have a few of the basics under your belt.

Preparation for Learning to Read Music

Formal note reading is not required in order to understand the basics of music. Younger children can learn musical concepts long before learning written notation. Applying some of the vocabulary and concepts from above will help you begin to discern some of the inner workings of music. The good news is that any type of music can be used for practice.

- Melodic Direction. Just being able to recognize whether a melody goes up or down is a big step, and an important auditory-cognitive process for children to undergo. Imagine the melody of a song such as “Row, Row, Row Your Boat.” Sing the song dividing it into two phrases (phrase 1 begins with “row,” phrase 2 begins with “merrily”). What is the direction of phrase 1? Phrase 2? Draw the direction of the phrase in the air with your finger as you sing.

- Timbre. Practice describing different timbres of music—play different types of music on Pandora, for example, and try to describe the timbres you hear, including the vocal timbre of the singer or instrumental timbres.

- Expression. Now practice describing the expressive qualities of a song. Are there dynamics? What type of articulation is there? Is the tempo fast, slow, medium?

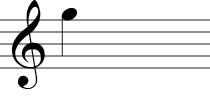

Learning Notation: Pitch

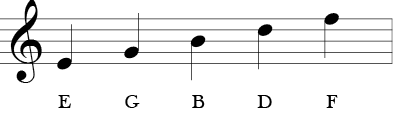

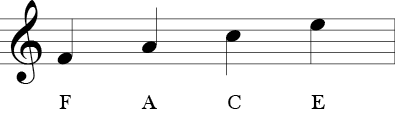

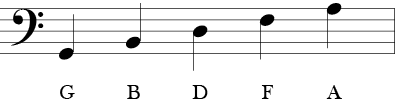

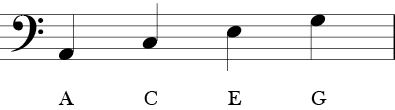

It sounds simple, but notes or pitches are the building blocks of music. Just being able to read simple notation will help build your confidence. Learning notes on a staff certainly seems dull, but coming up with mnemonics for the notes on the staff can actually be fun. For example, most people are familiar with:

- Every Good Boy Deserves Fudge to indicate the treble clef line notes

- F A C E to indicate the treble clef space notes

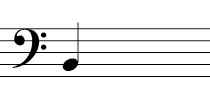

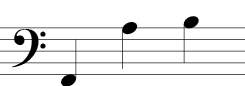

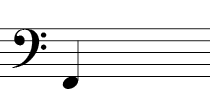

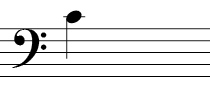

- Good Boys Deserve Fudge Always for the bass clef line notes

- All Cows Eat Grass for the bass clef space notes

- But allowing children to develop their own mnemonic device for these notes can a creative way to have them own the notes themselves. How about Grizzly Bears Don’t Fly Airplanes for the lines of the bass clef, or Empty Garbage Before Dad Flips or Elephants Get Big Dirty Feet for the lines of the treble clef?

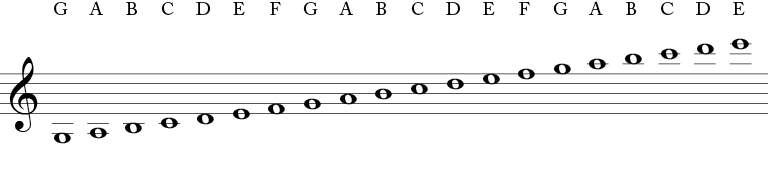

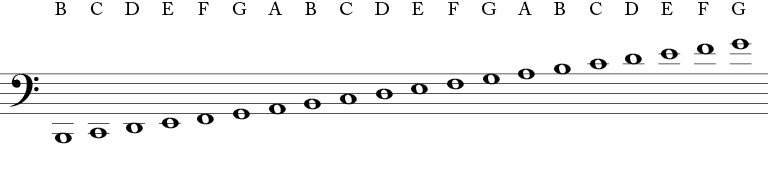

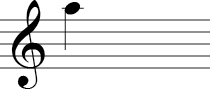

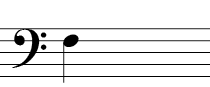

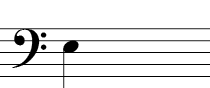

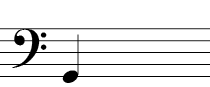

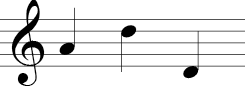

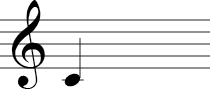

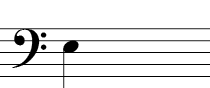

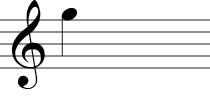

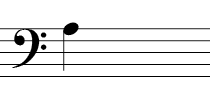

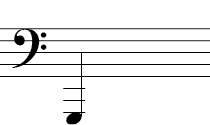

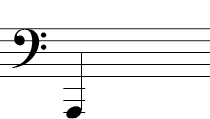

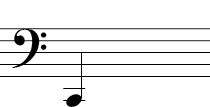

Notes of the Treble Staff

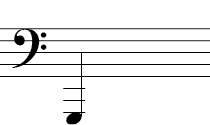

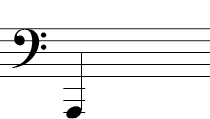

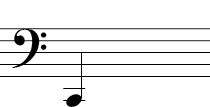

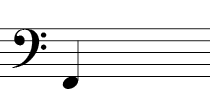

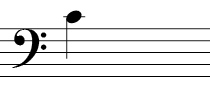

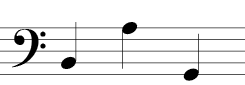

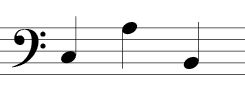

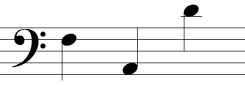

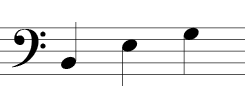

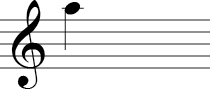

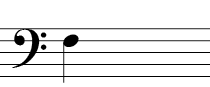

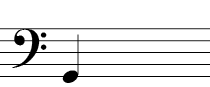

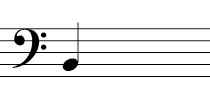

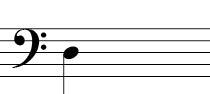

Notes of the Bass Staff

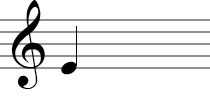

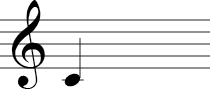

NOTE/PITCH NAME PRACTICE

NOTE REVIEW: SPELL WORDS WITH NOTES

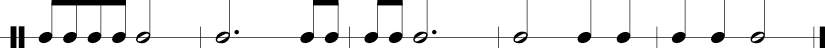

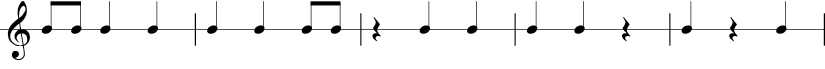

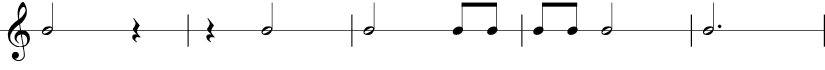

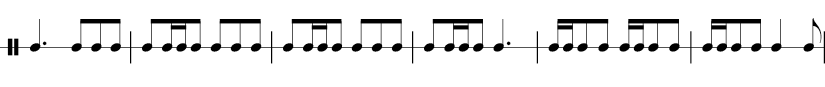

Learning Notation: Rhythm

Rhythm concerns the organization of musical elements into sounds and silences. Rhythm occurs in a melody, in the accompaniment, and uses combinations of short and long durations to create patterns and entire compositions. Rests are as important to the music as are the sounded rhythms because, just like language, rests use silence to help organize the sounds so we can better understand them.

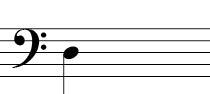

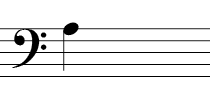

Notes and rests

Whole note  | Whole rest  |

Dotted half note  | Dotted half rest  |

Half note  | Half rest  |

Quarter note  | Quarter rest  |

Eighth note  | Eighth rest  |

Sixteenth note  | Sixteenth rest  |

RHYTHM PRACTICE: LABEL EACH RHYTHM

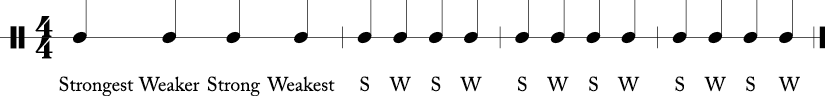

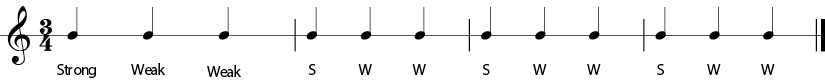

Learning Notation: Meter

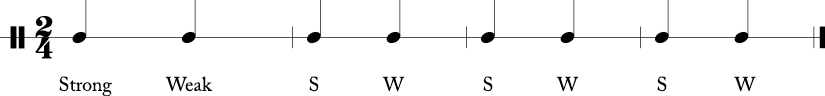

Meter concerns the organization of music into strong and weak beats that are separated by measures. Having children feel the strong beats such as the downbeat, the first beat in a measure, is relatively easy. From there, it’s a matter of counting, hearing and feeling how the strong vs. weak beats are grouped to create a meter.

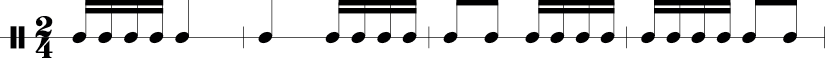

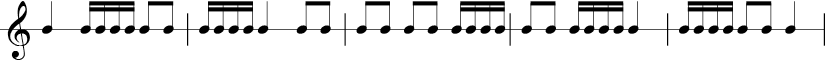

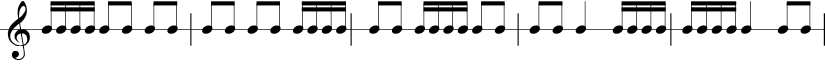

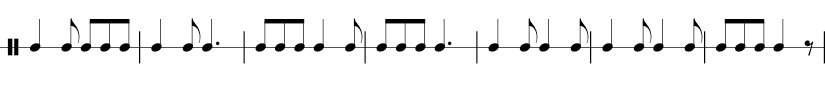

Duple Meters

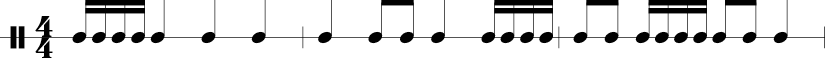

In duple meter, each measure contains groupings of two beats (or multiples of two). For example, in a 2/4 time signature, there are two beats in a measure with the quarter note receiving one beat or one count. In a 4/4 time signature, there are four beats in a measure, and the quarter note also receives one beat or count.

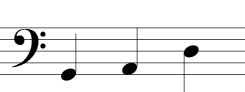

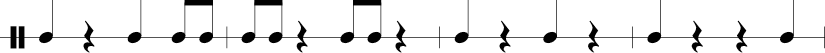

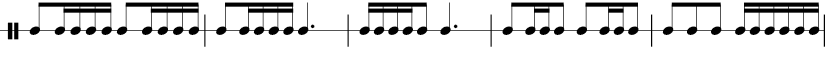

Examples of 2/4 Rhythms

Examples of 4/4 Rhythms

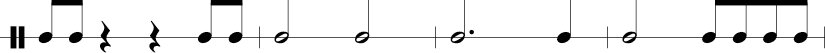

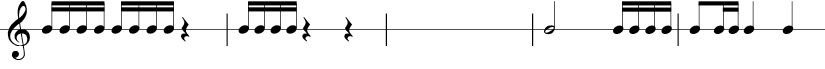

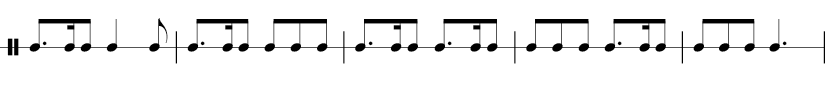

Triple Meters

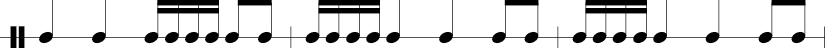

In triple meter, each measure contains three beats (or a multiple of three). For example, in a 3/4 time signature, there are three beats in a measure and the quarter note receives one beat.

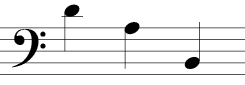

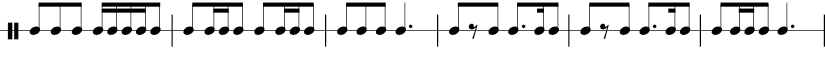

Examples of 3/4 Rhythms

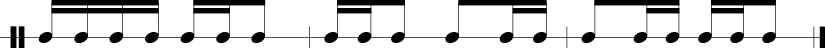

Compound Meters

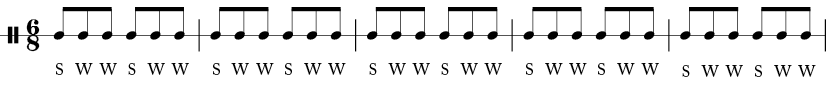

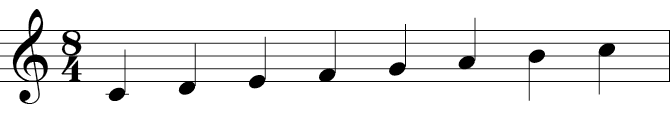

Both duple and triple meter are known as simple meters—that means that each beat can be divided into two eighth notes. The time signature 6/8 is very common for children’s rhymes and songs. In 6/8, there are six beats in a measure with each eighth note receiving one beat. 6/8 is known as acompound meter, meaning that each of the two main beats can be divided into three parts.

Examples of 6/8 Rhythms

s

Learning Notation: Dynamics

Learning some basic concepts of dynamics and tempo will allow you better access to involve children in music listening and making.

The two basic dynamic indications in music are:

- p, for piano, meaning “soft”

- f, for forte, meaning “loud” or actually, with force, in Italian

More subtle degrees of loudness or softness are indicated by:

- mp, for mezzo-piano, meaning “moderately soft”

- mf, for mezzo-forte, meaning “moderately loud”

There are also more extreme degrees of dynamics represented by:

- pp, for pianissimo and meaning “very soft”

- ff, for fortissimo and meaning “very loud”

Terms for changing volume are:

- Crescendo (gradually increasing volume)

- Decrescendo (gradually decreasing volume)

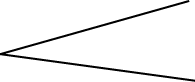

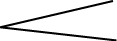

Crescendo

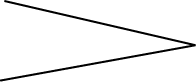

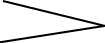

Decrescendo

DYNAMICS PRACTICE

Fill in the blanks below using the following terms: fortissimo, pianissimo, mezzo-forte, mezzo-piano, crescendo, decrescendo, forte, piano

1. p | |

2. f | |

3. ff | |

4. mp | |

5. | |

6. mf | |

7. pp | |

8. | |

Learning Notation: Tempo

Tempo is the speed of the music, or the number of beats per minute. Music’s tempo is rather infectious, and children respond physically to both fast and slow speeds. The following are some terms and their beats per minute to help you gauge different tempi. The terms are in Italian, and are listed from slowest to fastest.

- Larghissimo: very, very slowly (19 beats per minute or less)

- Grave: slowly and solemnly (20–40 bpm)

- Lento: slowly (40–45 bpm)

- Largo: broadly (45–50 bpm)

- Larghetto: rather broadly (50–55 bpm)

- Adagio: slow and stately (literally, “at ease”) (55–65 bpm)

- Andante: at a walking pace (the verb andare in Italian means to walk) (73–77 bpm)

- Andantino: slightly faster than andante (78–83 bpm)

- Marcia moderato: moderately, in the manner of a march (83–85 bpm)

- Moderato: moderately (86–97 bpm)

- Allegretto: moderately fast (98–109 bpm)

- Allegro: fast, quickly and bright (109–132 bpm)

- Vivace: lively and fast (132–140 bpm)

- Allegrissimo: very fast (150–167 bpm)

- Presto: extremely fast (168–177 bpm)

- Prestissimo: even faster thanpresto (178 bpm and above)

Terms that refer to changing tempo:

- Ritardando: gradually slowing down

- Accelerando: gradually accelerating

Scales

Scales are sets of musical notes organized by pitch. In Western culture, we predominantly use the major and minor scales. However, many children’s songs use the pentatonic scales (both major and minor) as well.

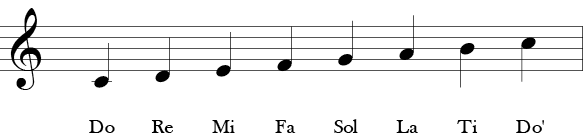

The major scale comprises seven different pitches that are organized by using a combination of half steps (one note on the piano to the very next note) and whole steps (two half steps together). The major scale looks as follows: Whole Whole Half Whole Whole Whole Half or W W H W W W H.

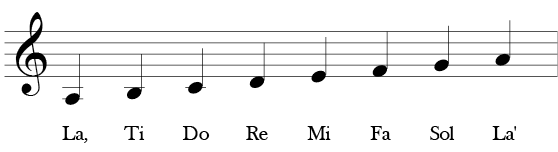

A minor scale uses the following formula: W H W W H W W.

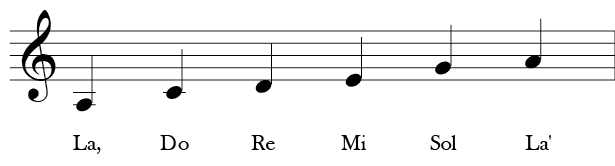

Pentatonic scales, found in many early American and children’s songs, only use five pitches, hence the moniker “pentatonic.” There are many types of major pentatonic scales, but one of the most popular major pentatonic scale is similar to the major scale, but without the 4th or 7th pitches (Fa or Ti). One of the common minor pentatonic scales is similar to the minor scale, but also without (Fa or Ti).

Major, minor (natural), and pentatonic scales

Major Scale (C Major)

Minor Scale (A Minor)

Major Pentatonic (C)

Minor Pentatonic (A)

SCALE PRACTICE

Label the half steps and whole steps for the C major scale.

Practice writing your own C major scale.

Label the half steps and whole steps of the A minor scale.

Practice writing your own A minor scale.

Resources for Further Learning

There are numerous websites that cover the fundamentals of music, including the staff, notes, clefs, ledger lines, rhythm, meter, scales, chords, and chord progressions.